Pakistani music faces significant challenges in reaching a wider audience and preserving its linguistic nuances. This project addresses these critical issues by aiming to increase the accessibility of Pakistani music for both local and international audiences. A core objective is to preserve the linguistic culture of Urdu by ensuring an accurate and authentic representation of the language. The primary outcome was the design and development of a user-friendly tool that supports multilingual, multiscript captions for songs, with a particular focus on Urdu and English as they are the official languages of Pakistan. This solution seeks to increase language equality in technology.

Urdu faces a significant technological barrier: it’s largely unrecognized by essential platforms like transcription software and music distribution services. A fundamental challenge lies in its right-to-left orientation, which clashes with the left-to-right design prevalent in Western technology. This mismatch creates a high learning curve for typing in Urdu, hindering its digital presence.

Furthermore, Nastaliq, the traditional and preferred Urdu script, presents display difficulties due to its non-horizontal baseline and other rendering complexities.

Consequently, users often resort to Roman Urdu – typing Urdu words with English letters. This informal practice, however, lacks standardization and contributes to the erosion of the language and its script.

The issue is compounded in Pakistani music, where songs now frequently blend Urdu and English, forcing technology to handle text in opposing directions.

This leads to a pervasive lack of online Urdu song lyrics, diminishing accessibility and listener engagement, as visual lyrics are crucial for retention. Musicians do not necessarily have the complete lyrics after production changes, nor do they have the time to transcribe them, especially given the fear of writing incorrect lyrics in their mother tongue.

.png)

A responsive website that enables users to upload music files for rapid, highly accurate transcription into Roman Urdu and English. It offers seamless conversion of Roman Urdu transcripts into Urdu script, and revert to Roman Urdu as needed. Comprehensive editing tools, including guidance on Urdu and transliteration keyboards, empower users to ensure linguistic precision.

For more details about the study you can continue scrolling.

.png)

Challenges in Urdu Digitalization

Difficulties in Automatic Lyrics Transcription

.png)

The study comprised three stages:

.png)

Songwriting Habits of Musicians

Mobile-First Approach: Musicians primarily use their phones for songwriting, leveraging the Notes app for storing, sharing, brainstorming, and archiving lyrics and ideas. Phones are preferred over laptops due to their accessibility and mobility, especially during creative flow states.

Time Constraints for Lyric Posting: Musicians recognize the value of posting lyrics, seeing it as crucial for audience engagement and song memorability—even likening it to "treating your songs as poetry." However, they often lack the time to write lyrics due to managing all aspects of their work independently.

Challenges with Urdu Lyrics

Reliance on Roman Urdu: Musicians often default to typing lyrics in Roman Urdu due to the difficulty of learning Urdu keyboard layouts and a lack of confidence in writing in the native script. This stems from a common background in English-medium education, where Urdu ceased to be a mandatory subject after a certain point.

Concerns About Urdu Accuracy: Musicians fear Urdu grammar/spelling mistakes more than English ones. Unlike English, errors in their mother tongue can feel incompetent, highlighting a need for strong Urdu language support.

Consumption vs. Production Mismatch: Despite difficulties in writing in Urdu script many musicians, particularly rappers, draw inspiration from written Urdu poetry. This creates a disconnect between their consumption and production of songs.

Script Preferences: Musicians generally couldn't name the Nastaliq typeface, but they could easily identify it and showed a strong preference for it over the Naskh script which is “robotic and boxed in”. This preference stems from their familiarity with Nastaliq and its aesthetically pleasing appearance.

Dynamic Nature of Lyrics & Collaboration

Fluid Lyrics: Musicians don't always have complete lyrics written down, as content can evolve during production or collaboration. Rappers, for instance, are often possessive about their lyrics and may freestyle, meaning final lyrics might not be fully documented even after production.

Structural Labeling Needs: While musicians may not always include song structure labels (like chorus, verse) when writing in their Notes app, these labels are required when uploading lyrics to platforms such as Musixmatch.

Perspectives on LLM Transcription

Openness to LLMs: Musicians are generally unconcerned about Large Language Models (LLMs) training on their songs for transcription purposes. They are open to LLM assistance in transcription, believing it can save them time.

Human Intervention Required: They don't expect lyric transcriptions to be completely or mostly accurate and humans will need to fix the lyrics particularly because of their prior experience with Urdu technology.

Urdu Technology Tools

LLM Capabilities for Urdu Transcription: Usama Bin Shafqat, an AI Engineer at Google, demonstrated Gemini's ability to handle less-documented languages in Pakistan and manage the musical complexity of multivocal group performances. Gemini achieved near-complete accuracy in transcribing both Urdu and Roman Urdu.

Prompt Engineering: However, as LLMs are likely to resort to the Roman Hindi form of transliteration, developing an Urdu-specific solution would require more strict prompt engineering.

Urdu Transliteration Keyboard: Sheikh Ahmed, an Urdu language specialist at Musixmatch, showed the importance of a Roman Urdu transliteration keyboard for transcribing songs. This tool is especially valuable for songs blending Urdu and English, as it enables him to type in Roman Urdu and instantly generate the correct Urdu script, all while seamlessly including English words without constantly switching between different keyboard layouts.

Urdu Keyboard Insights: Zeerak Ahmed, founder of Urdu keyboard (Matnsaz), shared insights from his research on technology adoption and pain points when typing in Urdu. He was also able to provide guidance on project direction based on his experience designing and developing Matnsaz.

.png)

Multi-script Transcripts: Lyrics to be provided in both Roman Urdu and Urdu (Nastaliq) to reduce friction in transcribing in both scripts.

Error Correction: Offer users alternative word suggestions in both Roman Urdu and Urdu, along with access to an Urdu dictionary, to help them write confidently and reduce the fear of making mistakes.

Alternative Input Methods: Provide speech-to-text technology for dictating lyrics and an Urdu transliteration keyboard to lower the barrier to accessing Urdu text technology.

Song Structure Labels: Enable users to select and apply predefined song structure labels (like chorus, verse) to quickly add finishing touches to their song transcripts.

Timestamped Transcripts: Integrate timestamp markers into transcripts, allowing musicians to convert their song transcripts into lyric videos faster within video editing software.

Audio-Playback Controls: Give users more control over transcription accuracy by providing song playback speed controls. This aligns with the mental models of other transcription software and would also benefit fans transcribing songs.

An MVP was developed to test Gemini’s real-time Roman Urdu song transcription capabilities and observe how users made corrections. Participants were also provided with a transliteration keyboard, which was a first-time experience for all of them. The songs were transcribed in Roman Urdu by default as it is the mental model for digital Urdu song lyrics.

.png)

Figma prototypes were created to test the necessity of all ideated features and to provide users with mobile-first layouts, aligning with their habit of songwriting on phones. To evaluate different display options for Roman Urdu and Urdu lyrics, participants were given two distinct prototypes: one where both lyric types coexisted on the same page, and another where users could toggle between the two.

.png)

Usability testing was conducted with both musicians and music enthusiasts, as they are the most likely users to transcribe song lyrics. Remote testing was necessary for participants located in Pakistan, given the researcher's location in the US. Designs were updated in iterations.

Key Observations & User Feedback:

.gif)

A final version of the website was created after incorporating user feedback. The Home page now also provides clear guidance for installing Urdu and transliteration keyboards, tailored to the user’s specific platform.

Key Feature Updates and Design Improvements

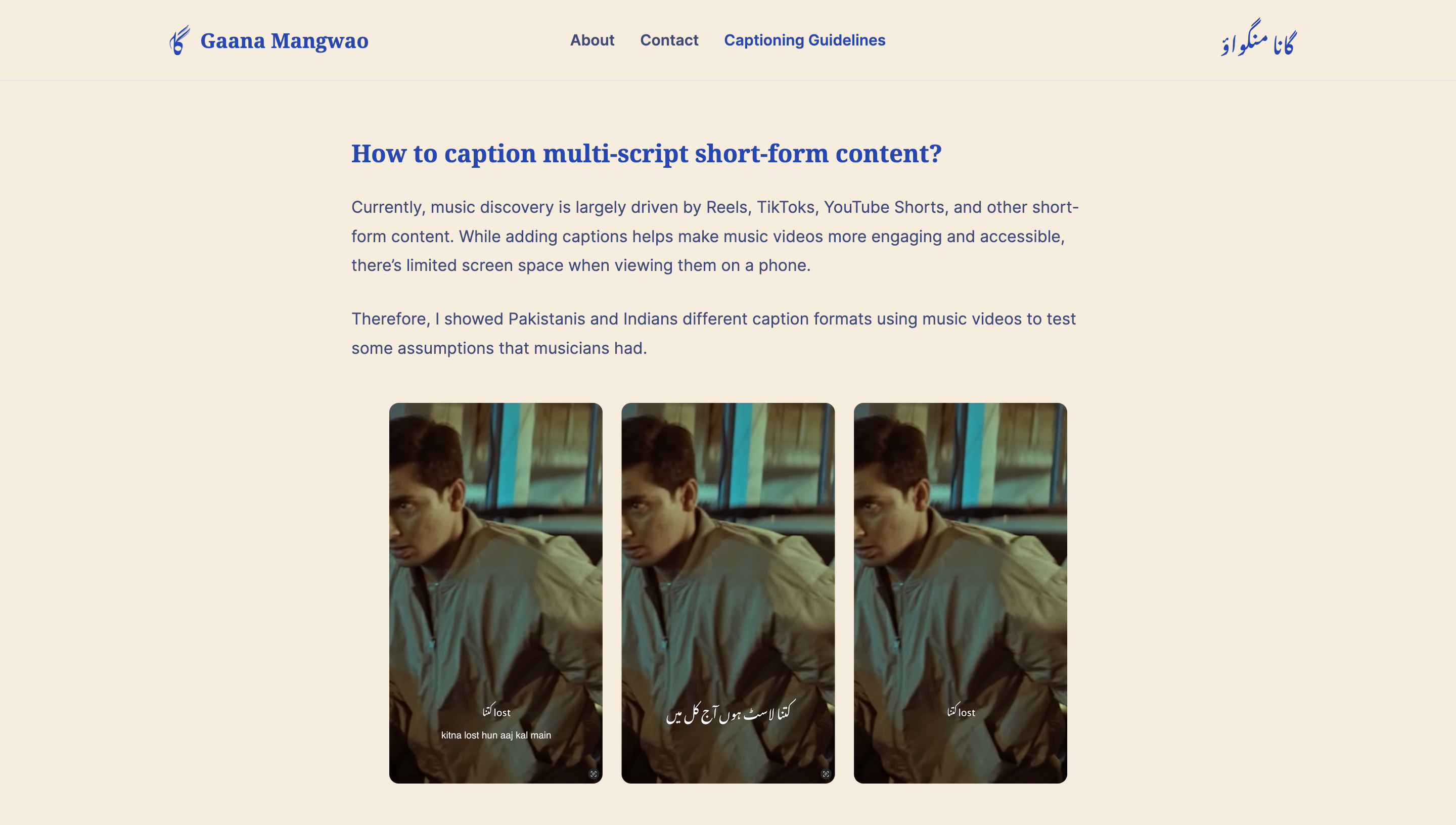

This part of the study aims to establish Urdu song captioning guidelines through testing multilingual, multi-script captions with both Pakistani and Indian audiences. Indians were considered as they form a large part of the Pakistani music fan base as Urdu and Hindi have a large phonetic overlap. But Urdu and Hindi scripts are completely different. As a result Roman Urdu/Hindi becomes a common ground.

Given that musicians indicated short-form content as a primary driver for music discovery, it was crucial to design for this experience, especially considering the limited digital space on mobile screens.

.png)

.png)

A mixed-methods study was conducted with Pakistanis and Indians music enthusiasts to do a visual design evaluation. This study also tested assumptions that musicians had provided in the primary research.

Visual and Emotional Impact of Urdu Script

Benefits of Dual-Script Display

Optimizing Script Presentation

Factors Influencing Script Preference

The study faced challenges in recruiting Urdu-medium artists and audience members, primarily because the researcher was located in the US during the study period. As a result, the findings are biased towards English-medium participants and may not fully represent the general population.

Due to time constraints, the number of participants for testing was limited. However, there are plans to expand participant recruitment after the product launch. Future development also includes extending the transcription tool to support other regional languages, such as Punjabi, Sindhi, and Pashto.

Finally, the multi-script captioning guidelines require more comprehensive development before they are disseminated. The goal is to share them through the Pakistani music magazine Hamnawa, which boasts a substantial readership of musicians.

Gaana Mangwao was possible because of the foundational work done by others before me and all of my prior experiences. It may seem obvious, but this project would have turned out very differently without the supervision of Dr. Rua Williams at Purdue; advice of Zeerak Ahmed, founder of Matnsaz and Hamnawa; Sheikh Ahmed's work at Musixmatch; Usama Bin Shafqat's experiments with LLMs; and all the musicians who were willing to give me their time despite a 10-hour time difference. As it turns out, AI can be used in a meaningful way. However, my biggest takeaway from this project is the importance of building a community.